ART

SOUL OF A NATION: ART IN THE AGE OF BLACK POWER AT THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM

WORDS

by MILENA DEDOVIC

WEB EDIT

by KRISTOPHER FRASER

PHOTOS

COURTESY of BROOKLYN MUSEUM

Whitney Young, an American civil rights leader said, “Black Power simply means: Look at me, I’m here. I have dignity. I have pride. I have roots. I insist, I demand that I participate in those decisions that affect my life and the lives of my children. It means that I am somebody”. Driven by the same urgency and thirst for innovation, black artists gathered across America in the 60s to use their art as a medium to emphasize racial pride and start the battle for the social and political rights. The shifting power of the creative process behind these masterpieces lead me through the room like an invisible force. All of these alluring artworks were calling out for attention, for their stories to be seen and heard.

Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power tackles two critical decades of the Black Power movement in America, giving us an insight into how it influenced American art during this revolutionary period. The show brings together a unique look at disparate ways black artists rebelled against their political and social circumstances. The engaging artworks on the walls tell the stories of more than 60 African American artists and take us a step back in time to manifest the development of their art techniques across the country.

Benny Andrews (American, 1930-2006). Did the Bear Sit Under a Tree?, 1969. Oil on canvas with painted fabric collage and zipper, 50 x 61 ¾ x 2 ¼ in. (127 x 156.8 x 5.7 cm). Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York. Emanuel Collection © 2018 Estate of Benny Andrews/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York, NY

The story begins in 1963, a moment just before the emergence of the Black Power movement. The Spiral Group, a New York-based collective of 15 painters, was trying to find a united voice that would represent their mutual tendencies of relating their art to current political goals and creating a collective “Negro” aesthetic. Even though the group ultimately did not agree on a comprehensive aesthetic, they managed to mount one group show in 1965 with the single organizing principle – all of the artworks should be in black-and-white, with both social and aesthetic reference. And they proved their point, these pieces were hauntingly attractive.

The following years after the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom were marked with violent events, assassination of political leader, Malcolm X and bloody protests. Art was under the influence of the sociopolitical events. The colors changed - instead of black-and-white aesthetic, vivid colors became dominant. Symbols were growing out of resistance to oppression, such as the Black Power fist and the bleeding American flag. Art was all about critique and activism.

Wadsworth A. Jarrell (American, born 1929). Revolutionary (Angela Davis), 1971. Acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 64 x 51 in. (162.6 x 129.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of R. M. Atwater, Anna Wolfrom Dove, Alice Fiebiger, Belle Campbell Harris, and Emma L/ Hyde, by exchange, Designated Purchase Fund, Mary Smith Dorward Fund, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, and Carll H. de Silver Fund, 2012.80.18. © Wadsworth A. Jarrell. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

Walking around the gallery, a conspicuous painting drew my attention. The Flag is Bleeding by Faith Ringgold features American citizens in a bleeding flag, symbolizing the country’s violence. Ringgold’s work was created in her unique style, ‘super realism’, committed to depict the oppression faced by black people. When Amiri Baraka, an African American writer stated, “The artist’s role is to raise the consciousness of the people. To make them understand life, the world and themselves more completely. That’s how I see it. Otherwise, I don’t know why you do it”, Ringgold found inspiration for her art in his words.

Everybody had the urge to express themselves in their own, unique manner. Some were communicating through geometrically shaped lines, optical illusions and variations of shape, while others were experimenting with assemblage and sculpture. It was all a way of sending a message. Through the eyes of Kay Brown, then-president Richard Nixon wears the devil’s red attire as he uses black children as pawns in a game, while the black activist Malcolm X hovers on the left. She chose the persuasive power of the collage to communicate visually. Her piece The Devil and His Game strikingly fills up the room with a gruesome ambience.

Elizabeth Catlett (American, 1915-2012). Black Unity, 1968. Mahogany wood, 22 ½ x 20 ¼ x 12 ½ in. (57.2 x 51.4 x 31.8 cm). Crustal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas. © Catlett Mora Family Trust. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY

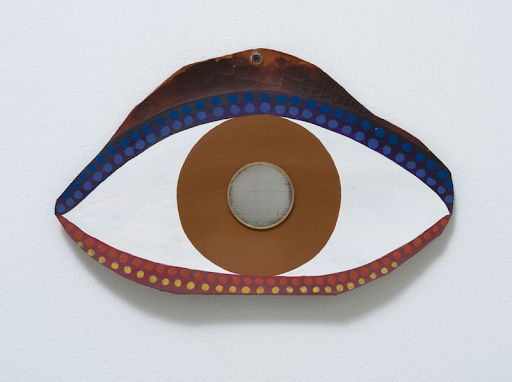

Betye Saar (American, born 1926). Eye, 1972. Acrylic on leather, 8 ½ x 13 ¾ in. (21.6 x 34.9 cm). Collection of Sheila Siber and David Limburger. © Betye Saar. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles-based

“Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power tackles two critical decades of the Black Power movement in America, giving us an insight into how it influenced American art during this revolutionary period.”

The late 60s and early 70s brought aesthetic innovations across abstraction and figuration in painting and sculpture. But, the inconsistency between the two resulted in raising questions between black artists – should all art be socially engaged? A new sense of a revolutionary act occurred at this moment, when artists approached the idea of painting the black figure, rarely seen in European and American fine art before. For a greater emotional impact, Dana C. Chandler expressed his protest against the Chicago police’s killing of Fred Hampton in a peaceful protest, by using an actual door riddled with bullet holes, called Fred Hampton’s Door 2. The art peace stands in the room amongst others, calling us to turn the door handle and witness this infamous event.

The exhibition draws to a close with the work of avant-garde black artists such as Lorraine O’Grady, David Hammons, Senga Nengudi and others, leaving a lingering thought of Wilma Rudolph’s triumphal expression: “Never underestimate the power of dreams and the influence of the human spirit. We are all the same in this notion: The potential for greatness lives within each of us.”

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power will be on view September 14, 2018 through to February 3, 2019, at the Brooklyn Museum.

Betye Saar (American, born 1926). The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972. Wood, cotton, plastic, metal, acrylic, printed paper and fabric, 11 ¾ x 8 x 2 ¾ in. (29.8 x 20.3 x 7 cm). © Betye Saar. Collection of Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, California; purchased with the aid of funds from the National Endowment for the Arts (selected by The Committee for the Acquisition of Afro-American Art). © Betye Saar. (Photo: Benjamin Blackwell. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles)

Carolyn Lawrence (American, born 1940). Black Children Keep Your Spirits Free, 1972. Acrylic on canvas, 48 ½ x 50 ½ x 5 ¼ in. (123 x 128 x 13.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist. © Carolyn Mims Lawrence. (Photo: Michael Tropea)

Romare Bearden (American, 1911-1988). Pittsburgh Memory, 1964. Mixed-media collage of various printed papers and graphite on board, 8 ½ x 11 ¾ in. (21.6 x 29.8 cm). Collection of Halley K Harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld. © 2018 Romare Bearden Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

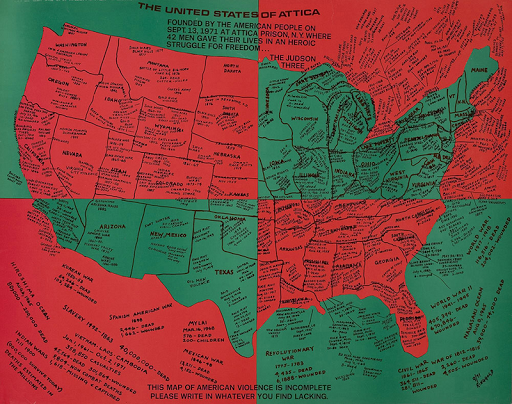

Faith Ringgold (American, born 1930). United Stated of Attica, 1972. Offset lithograph on paper, 21 ¾ x 27 ½ in. (55.2 x 69.9 cm). © 2018 Courtesy of ACA Galleries, New York. © 2018 Faith Ringgold, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Barkley L. Hendricks, (American, 1945-2017). Blood (Donald Formey), 1975. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 50 ½ in (182.9 x 128.3 cm). Courtesy of Dr. Kenneth Montague | The Wedge Collection, Toronto. © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum)

MORE FROM AS IF

© 2018, AS IF MEDIA GROUP

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

AS IF MAGAZINE

ABOUT

CONTACT

NEWSLETTER

PRIVACY POLICY

TERMS OF USE

SITE MAP

SUBSCRIPTION

SUBSCRIBE

CUSTOMER SERVICE

SEND A GIFT

SHOP

PRESS CENTER

ADVERTISING

IN THE PRESS

GET IN TOUCH

FOLLOW US

YOUTUBE

.jpg)