ART

MEET JONAS MEKAS, THE FILMMAKER WHO STARTED A QUIET REVOLUTION

With an intro from esteemed art curator Francesco Urbano Ragazzi, the Lithuanian-American filmmaker recalls his journey towards filmmaking and how he ignited an entire genre.

PORTRAIT AND INTERVIEW

by TATIJANA SHOAN

INTRODUCTION

by FRANCESCO URBANO RAGAZZI

ALL ARTWORK

by JONAS MEKAS

Jonas Mekas is one of the great pillars of avant-garde filmmaking, the author of nearly 100 movies, which gave shape to a film genre called film diary, and most importantly, he may be the happiest man in the world. This comes from being in the right place at the right time: Manhattan in the 60s. But Mekas’ happiness is not a fluke, but an exercise the Lithuanian-American filmmaker has committed to for 95 years—after all, his life did not have an easy start.

Jonas was born in 1922 in the village of Semeniškiai, Lithuania. At the age of 22, he was taken by the Nazis while trying to reach Vienna with his brother, Adolfas. The brothers were placed in the Elmshorn forced labor camp, where he started writing a diary that later became the book, I Had Nowhere to Go, and a powerful movie directed by Douglas Gordon. In the book, he recalled his rocambolesque escape to Sweden a few months before the end of WWII, and how, afterwards, he and his brother lived in the refugee camps of Wiesbaden and Kassel for four more years. The turning point came in 1949 when the humanitarian organization of the UN brought Mekas to New York, the city that saved their sanity, as the artist often recalls.

Just two weeks after his arrival, Mekas borrowed money to purchase his first Bolex, a camera he employed for filming almost every day for 40 years. Meanwhile, his interest for cinema grew, and in 1954 he founded Film Culture magazine, and became the first cinema critic for The Village Voice. He was also actively organizing avant-garde film screenings that Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono, Allen Ginsberg and Susan Sontag would attend. Incidentally, the young refugee became the catalyst for an entire generation of filmmakers who reunited to fight against the ethics, aesthetics and distribution standards of classical Hollywood.

From this exuberant energy, the New American Cinema Group/The Film-Makers’ Cooperative arose and, in 1960, Mekas wrote its manifesto. Film formats then exploded. Some films were now six hours long, while others lasted less than two minutes. Others needed several screens and projectors to be shown. A revolution had begun! Yet with every revolution, there are casualties. The audiences did not always understand what they were seeing, and Jonas was actually arrested on obscenity charges for screening films considered obscene.

After enduring the tragedy of war and exile, the filmmaker decided to film the happy moments of his existence. It is with this vision that he captures objects, landscapes, and relationships that we can see in his films Walden, Sleepless Night Stories, and As I Was Moving Ahead I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty. His multi-media show, Again, Again It All Comes Back To Me in Glimpses, is also currently on view at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul, Korean. Below, the artist looks back on his prolific career.

AS IF: Did your experiences as a displaced person solidify the power of photography for you?

Jonas Mekas: My early life experiences had nothing to do with my interest in photography or film. From as early as age six, I was only interested in poetry. Photography and film remained outside of my interest until much later. I saw my first film when I was 15.

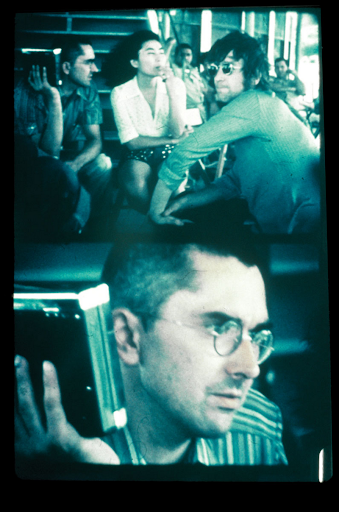

George Maciunas, Yoko Ono, and John Lennon on a Hudson River Fluxus cruise, New York, July 7th, 1971

Do you remember that film?

It was an insignificant American melodrama, and a Disney Mickey Mouse cartoon. The cinema was not part of my childhood because I grew up on a farm far from the city. We had no electricity, we had no radio, no telephone. I later ended up in a German forced labor camp and, after the war, in the displaced persons camp for four years with my brother Adolfas.

In late 1949, you were brought to New York. What was that like?

I arrived in New York at the right time. Everything was about to change in the arts. I caught the tail end of the classical period—Balanchine, Martha Graham, Tennessee Williams, Elia Kazan, Brando. It was just before the real explosion of the new! The happenings: theatre, action painting, Yvonne Rainer, John Cage, Buckminster Fuller, the Beat Generation, Fluxus. That's when things became really exciting. And this was still before Warhol! I totally submerged myself into it, I opened myself up to all that was new and emerging. I was so lucky to be thrown out of my village, and out of my country, and that I went through the war and the miseries of the postwar years to end up in New York, here, in the heart of everything.

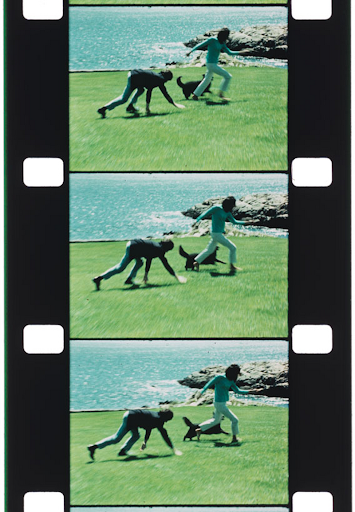

John Lennon and Yoko Ono during the filming of Legs, a film by Yoko Ono, 1970 | Jonas as a dog, with Minnie Cushing, Newport 1967

How did the poet become a filmmaker?

I had read about cinema before I came to New York, but I discovered it in New York. I continued writing poetry, but cinema moved into my life. I was searching and (was) a little bit lost until fate led me to the diaristic cinema. Novelists (and) narrative film-makers spend a lot of time on a subject, they develop themes and characters, but poets don’t stay long on any subject. We just pick up intense moments of reality, memory, feelings. The diaristic form and content of my films is made up of little poems, haikus strung together.

From being a cameraman on Warhol films to filming Dali’s street happenings, who has made the greatest impact on you?

They were all extraordinary people: Warhol, John Lennon, Salvador Dali, George Maciunas; each one was important. These were all very intense people whom I had the fortune to work with, and each of them contributed something completely unique to our culture and life.

“I am very open to situations that are totally new. They provoke me to go into unpredictable directions.”

(Martin) Scorsese said that you're not just preserving memories, you're preserving freedom. Do you agree with that?

To me, to be free is a very normal state of being. He may be referring to the screenings for which I was arrested. But for me, it was very normal to screen Flaming Creatures directed by Jack Smith, or Jean Genet’s film Un Chant d'Amour. Both films at that time were controversial and forbidden. But both are also important works of cinema, and both have contributed much to the understanding of what we are and our enjoyment of life. I knew their importance.

But you knew you were breaking the law. Is that why you found it important to do?

I did not think about the law. It did not exist, for me. I thought only about the films, their beauty, and I wanted to share them with others. It’s very funny, the guy who prosecuted me for screening Flaming Creatures in 1964, Gerald Harris, wrote me a letter not long ago, to apologize for it. I sent his letter to The New York Times, and they published it. It takes courage to do what he did. You know who testified in my defense at the court? Susan Sontag and Allen Ginsberg. But it was of little help. It’s one’s duty to do the right thing if one feels it is the right thing to do.

Watercolor of the Anthology Film Archives lobby at 425 Lafayette Street, by Jerome Hill

In New York you founded Film Culture magazine. Tell me about this publication.

There were several good film magazines in Europe. In France there was Cahiers du Cinema, and England had Sight and Sound. But there was nothing in the United States. In New York, I was meeting many young people who loved cinema, wanted to talk about movies, exchange ideas, argue. We needed a platform for it.

What's the key ingredient for avant-garde film?

The term “avant-garde film” traditionally refers to the private, personal, non-commercial, usually non-narrative, “poetic” films. What's the key ingredient for an “avant-garde film”? Same as for any film: intensity, richness of content, all the qualities that make you want to see it again and again, and you want to share it with friends—and every time you see it, it gives you something else. It survives time with no loss, and actually grows in importance.

With Hollywood films, the saying goes, “If you have a good script, you have a good movie. Without a script, there’s no movie.” This is very different with avant-garde film.

A script doesn’t make a good movie! No! (laughs). There are very good scripts that turn into very bad films, some so bad that they don’t even get released.

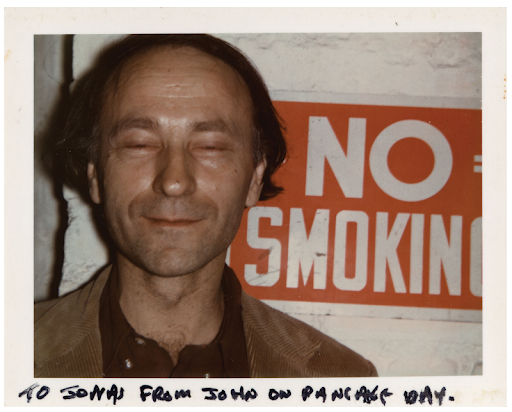

Polaroid of Jonas Mekas by John Lennon, New York

Finish this sentence for me. I am a filmmaker because...

Because I cannot not be a filmmaker. It’s a necessity. I don’t do anything unless there is a necessity. Film Culture magazine was started because of a necessity. I joined the Village Voice in 1958 as their film writer because there was a new generation of filmmakers emerging in New York but nobody knew about them, so I had to bring them to the public attention. That’s how my column, Movie Journal, began. I also began curating screenings so people could see the films I was writing about. There was a necessity to do that because I thought these films were beautiful and special. They gave the viewer something they couldn’t get from commercial cinema. The first programs included Kenneth Anger, Sidney Peterson, Whitney Brothers, Maya Deren, early Markopoulos—now all classics.

Through your recent book, A Dance with Fred Astaire, I learned that Jackie Kennedy hired you to teach John and Caroline filmmaking.

She wanted her children to know more about art history and photography, so she engaged Peter Beard to tutor them in art. But she thought they should also know about cinema. So, she asked Peter to recommend someone to introduce them to it, and Peter suggested me. Jackie was living in another world totally different from mine, obviously! She had a big, big life, had been on television, in newspapers, and travelled the world on official presidential business. I didn’t know how she would respond to me and my work, but she responded very positively.

Jonas with Andy Warhol at the Factory, New York

I recently went to the New York Missoni boutique installation. It features a lot of floral imagery. Tell us about that.

I thought it was challenging, so why not? I am very open to situations that are totally new. They provoke me to go into unpredictable directions. Plus, a boutique is open to all people. It’s not a museum or gallery. I grew up with flowers in the country. I am a farmer boy. Our village had an old woman who was a healer, and healed with dried flowers. I knew all of the flowers within several miles around the village, so she chose me to gather the flowers that she needed. Flowers are very much a part of my life from childhood. Plus, Missoni is very much about color. Blue, Yellow, Red, Purple is the name of the installation. It came to me in a dream.

You’ve done public installations before, though.

I worked with curator Francesco Urbano Ragazzi in Venice for the Biennale two years ago, where we did an installation at the Venice Burger King. There is only one Burger King in Venice and that’s where I had my show. Originally, the owner was very skeptical, but when more and more people began coming there to eat because of the installation, they asked me to keep it there. I covered all 32 panels of their windows with colored film frames, so when you enter, you are walking into a stained-glass space of 768 images.

MORE FROM AS IF

© 2018, AS IF MEDIA GROUP

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

AS IF MAGAZINE

ABOUT

CONTACT

NEWSLETTER

PRIVACY POLICY

TERMS OF USE

SITE MAP

SUBSCRIPTION

SUBSCRIBE

CUSTOMER SERVICE

SEND A GIFT

SHOP

PRESS CENTER

ADVERTISING

IN THE PRESS

GET IN TOUCH

FOLLOW US

YOUTUBE