ART

WHY RAN ORTNER’S VIVID OCEAN PAINTINGS ARE MAKING WAVES

The self-taught artist offers up serene works via his dimensional paintings of oceans.

PORTRAIT AND INTERVIEW

by TATIJANA SHOAN

ALL ARTWORK

by RAN ORTNER

The sea, by its very nature, is sublime and abstract—Ran Ortner’s works dive right into that. Inspired by his life as a surfer and motorcycle racer, the artist’s vivid paintings of undulating waves capture the ocean’s constant tempo (as well as the ominous presence of what lies underneath). Below, the artist talks his creative process.

AS IF: Tell me about your artistic practice?

Ran Ortner: As an artist, that’s a question I’m constantly living, and I think I have to keep living it. You have to keep a beginner’s mind because if you stay with that, everything is interesting. Most practices, whether you’re a ballet dancer, a motorcycle racer, a surfer, a painter, you have to practice again and again. As James Joyce says, for the millionth time. I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience.

You’re a self-taught artist. How many years of trial and error did you go through to understand how to find the symphony with light, color, and contrast?

I’m self-taught, but the better way to say it is that I’m not formally taught. From the museums I visited, books I’ve read, conversations I’ve had, the endless research I’ve done, and the hours upon hours of practice, I’ve definitely had some training. This process is ongoing. I read somewhere that one’s capacity to be an artist is directly related to one’s capacity to bear frustration (laughs)! I’ve always had a drive, and I’ve always been fascinated by potential, the reach for more capability, more engagement, more precision.

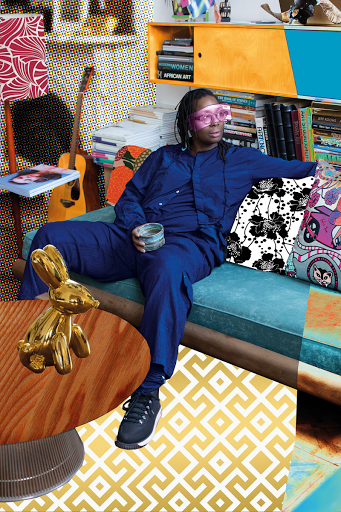

Ran Ortner Portrait by Tatijana Shoan

What ignited your interest in painting water?

My first bicycle became my wings, and from there I moved to motorcycles. I learned to ride very young and with so much fervor. I had so much built-up rage that I rode with a vigorous aggression. It was my release, my wings, my ecstasy—it was really quite an extraordinary experience. Riding was my first exposure to the potential of pulsing surges, which is what led me to the water. After motorcycling, I went heavily into surfing. The first five years of my life were in California and I was mesmerized by the surfers. I saw them as mystic creatures, these sinewy shaggy men returning from the depths. When I moved back to California at 19 or 20, surfing became my vehicle, and although it’s much safer than motorcycles, I find it much more terrifying. Big waves are incredible, when you’re held underwater you can’t breathe. The violence, the turbulence, the pressure. It’s the worst kind of beating, and the most beautiful relationship between heaven and hell.

And this is what draws you to the ocean?

First, there’s the experience of threshold that we each have as individuals. We’re in this constant space of navigating between what is visible and what is invisible. Our personality is invisible, but our body is visible. Our intent is invisible, but what we accomplish with our intent is often visible. The ocean is always asking us what lies beyond what we can see. There’s something deep, something beyond appearance. What’s extraordinary about the ocean is that the invisible, which is the wind, is becoming visible in the surface of the water. So, the surface is extraordinarily receptive. You see this assertively, aggressively, receptive energy. We don’t often think of receptive as powerful, and yet it is. Oftentimes the ocean is referred to in the feminine, and this receptive intensity is part of that. I see this in the ocean as it takes in these extraordinary surges of energy. I think water suggests the notion of opposites in such an elegant way. Early ocean paintings were always about peril. It’s amazing how something can be so terrifying and perilous, yet in the very same moment effervescent, delicate, and nurturing. The ocean is where we go to heal our wounds, to convalesce and restore, yet there’s something mournful about the ocean, a feeling of lament. As quickly as one connects to this lament, there is a relentless generosity. The ocean is always saying there’s more. It mirrors the constant rhythms of life. Humans are a collision of opposites—we have a desire for peace yet we’re easily violent; we have a desire for security, yet we’re easily bored. Also, the ocean is such a potent totem to the irrational—it’s pure revelry.

“Humans are a collision of opposites–we have a desire for peace yet we’re easily violent; we have a desire for security, yet we’re bored.”

How do you keep approaching the subject of water—the same subject—with a new outlook?

The compulsion of continued exploration. I see the paintings as explorations, and so the process of discovery stays rich, invigorating and fascinating. I’ve painted the ocean so many times, yet I feel I’m at the very beginning of touching what’s there. It was Goethe that said, few of us have the imagination for reality. Reality is the most surreal thing anyone ever came up with!

Release, 500 lbs of sand pouring from the wall, 2001

You hang your diptychs and triptychs up against one another which gives the illusion of one painting with black lines running through them. It’s not until you come closer to the painting do you see that it’s two or three canvases. I want to ask you about your decision to disrupt the composition by placing the diptychs and triptychs like that.

I’m intrigued by literature, and I’m always extraordinarily touched by these amazingly cool dead people that have left us their legacy in literature. When you read Dickens you’re communing with him, and I love the spine of books. For me, the paintings are literary references, especially the diptychs. It’s a real compositional no-no to have something right down the center of a painting. So, to have this disruptive line, like the spine of a book, right down the center is not a seamless perception of something, it’s a poetic iteration. I was in my 20’s when I became frustrated while painting, so I took my paintbrush and punctured my canvas and was fascinated by the potential of that. Then I started cutting the canvas and thought it was brilliant. A year or two later I was looking through an art book and saw Lucio Fontana’s work and he was doing canvas cutting the year I was born! Jasper Johns was once asked what the difference between working as a mature artist and a younger artist was, and he answered, as a mature artist I’m no longer surprised when my work looks like other people’s. We’re all connected to these archetypes, we’re all drawing from the rich experience we have in common which is being human.

I want to ask you about your work with sand. Is that an extension of your connection with the sea?

It’s not an extension of my connection to the sea, it’s an extension of my fascination with threshold. I keep exploring the thresholds between all the drives and energies in me, and then the resulting actions. What’s fascinating about sand is that it’s a solid that behaves as a fluid. Dunes are shifting, moving, rising and falling like ocean waves, but on a much slower timeline. There’s something in the rhythm of these movements in water and in sand, that suggest our embodied experience. From within my own body as a container, I must reach outside to connect, to commune, to touch someone else. We must break out of the container of self and that threshold into the larger world. It is so central to who we are.

“I want viewers to look, to ask themselves how they feel when they engage with a painting.”

What type of art do you most identify with?

Kafka said of his work that he wanted it to be the axe for the frozen sea inside, to break through the white noise. I don’t like realism, which is interesting because my paintings could be categorized as realism. The problem with realism is that generally attempting to fix something, and I’m interested in the opposite. I’m interested in unfastening. I know my paintings don’t really work until they’ve become unfastened. I’m always trying to get the surface of my work to be dynamic, where the dance of these rhythms become more than the sum of their parts and it feels like a symphony. I really feel them as symphonic. I love work that has rigor and deep consideration. I’m a big proponent of this line by Dickens: please, sir, I want some more? I would like some more.

Do you have any exhibitions coming up?

I’ve just received the 2018 Ellen Maria Gorrissen Fellowship from the American Academy in Berlin. I’ll have an exhibition of the work in Berlin. I would like to find a brutal, arcane piece of architecture to do a big sand piece. A monumental sand piece and a monumental painting.

I want to understand a little more about your childhood. I know your father was a violent man and moved your family from California to Alaska when you were a child. Can you tell me what your strongest childhood memory is?

My father got his pilot license the day before he piled us all in his 1949 Cessna. We took off from the little airstrip in Half Moon Bay near Pacifica where we lived and headed for Alaska, using binoculars to navigate. We read the road signs with binoculars from the plane. When we ran out of gas we landed on gravel roads and filled up at the gas station, the plane would run on regular premium gas! It’s quite fantastic we survived it all. My father was also a religious fanatic, so he would fly us to South America on preaching trips. When we prepared for the trips, he would make us all stand in a line holding what we wanted to take with us for the four months we’d be gone. We were only allotted something like seven pounds per person. Anything over the weight limit, we could not take, whether it was toothpaste or schoolbooks. My childhood was alternatively beautiful and terrifying. The beauty of Alaska and South America was extraordinary. It was terrifying because of my father’s violence, because of the lack of having any kind of personal sovereignty, and being powerless against larger forces. But, I wasn’t entirely powerless, I was able to preserve my imagination.

Element No. 2, oil on canvas, triptych, 72” x 234”, 2018

Element No. 3, oil on canvas, triptych, 72” x 234”, 2013

And your mother?

My mom had all three of us by the time she was 21, so she was a child herself. Sadly, my father’s violence dominated her world, so it was really like there were four kids, my mom being the eldest.

What is your ultimate goal when you’re working, and what is it that you want viewers to experience and walk away with?

I want viewers to look, to ask themselves how they feel when they engage with a painting. We’re such emotional, feeling creatures, but we get intoxicated with how smart we think we are and we’re often distanced from how we’re feeling. I think art asks us to feel.

MORE FROM AS IF

© 2018, AS IF MEDIA GROUP

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

AS IF MAGAZINE

ABOUT

CONTACT

NEWSLETTER

PRIVACY POLICY

TERMS OF USE

SITE MAP

SUBSCRIPTION

SUBSCRIBE

CUSTOMER SERVICE

SEND A GIFT

SHOP

PRESS CENTER

ADVERTISING

IN THE PRESS

GET IN TOUCH

FOLLOW US

YOUTUBE